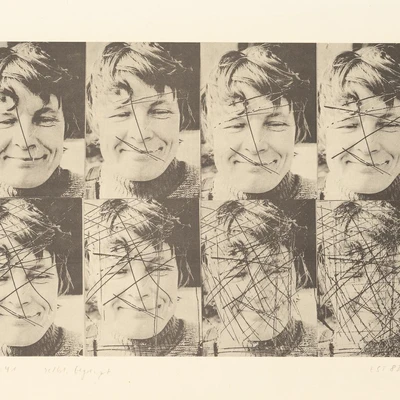

Charlotte Elfriede Pauly

- * 1886

- † 1981

Life dates

- Artist

Category

Fascinating Globetrotter with an Eye for the Poetry of the Everyday

Among a significant part of the East German artist generation coming of age in the 1960s, the small and feisty Charlotte E. Pauly, then already in her seventies, inspired a special fascination. Pauly had already made a name for herself as artist in the 1920s and 1930s with drawings and watercolors she made in the course of her voyages through Spain, Morocco, Portugal, and the entire Mediterranean region. "Especially for the younger artists, those who had seen hardly anything of the world, the vivid stories told by the 'great traveler' Charlotte Pauly conjured up, geographically and spiritually, a world that was to remain closed off to them for a long time to come."[1] Thus writes the fellow artist and friend Dieter Goltzsche, who – together with the GDR art critic Lothar Lang – furnished crucial long-term support to the life-long outsider Pauly.

Like perhaps no other German artist of the 20th century, Charlotte Pauly recorded and reflected on her lived experience in her work and cultivated through it an exotic "poetry of the everyday." Nevertheless, more than a few viewers saw in her straightforward-direct portrait drawings of farmers and fishermen, redolent of Heinrich Zille and Käthe Kollwitz, in her organic-cubist oil paintings of Spanish boys leading mules, or in the bright, scintillating Mediterranean watercolors that became her trademark only idiosyncratic dilettantism. Pauly, however, born 1886 in Stampen in Lower Silesia, became one of the first women in Germany to earn a doctoral degree in art history, studying in Stuttgart, Munich and Berlin during and after the First World War. She found her forms of crystalline simplicity and nobly arid painting style in the course of her travels, extending over several years, with the cubist Daniel Vázquez Díaz. But it is self-evident that there would be some friction between the state and an artist who saw it as her mission to cultivate a humanity of form, and who believed she had found, 20 years before the founding of the GDR, the paragon of freedom in the gypsies she portrayed. Commissions, moreover, that is working on command, never sparked her interest and so led to anemic results.

Pauly’s contemporaries were impressed by her motifs of human figures, which they had an opportunity to view in the atelier parties she regularly held. Her apartment in Friedrichshagen, which Wolf Biermann described as the "wildly romantic bohemian pad of an aged globetrotter," became a meeting point for a number of young intellectuals. And no wonder: Whether the question concerned politics or aesthetics, the Nazi state of yesterday or the Socialist spy-state of her era, Pauly never cow-towed to the party line. She had the courage to speak the truth, even unbidden, to the face of anyone. Having gained her reputation – and immediately thereafter her infamy as the "gypsy painter" – in 1933 in Breslau, the Silesian artist was able to flee, one year after the end of the war, from the homeland thenceforth administered by Polish authorities to war-torn Berlin, thanks to a Soviet special train organized to convey the legacy and corpse of her artist and writer friend Gerhard Hauptmann. Pauly was, however, always critical of what western civilization called progress, and she found the technologized city repulsive. For this reason, the self-styled country bumpkin moved to the village-like ambience of Berlin-Friedrichshagen and retreated once again into interior emigration. She shifted her artistic activity to writing – although she never published any of the numerous poems, novellas, short stories and novels written in this period.

Charlotte Pauly obtained recognition for work again only at the age of 75, when her friend, the graphic artist Herbert Tucholski, encouraged her to reproduce her early travel sketches as prints, lithographs, or etchings. Always ready for new adventures and always in search of direct and simple modes of expression, Pauly re-invented herself with the printing press and lent her memorializations of Oriental traders, Andalusian harvests and Portuguese dockworkers on the Mediterranean an even more expressive form. She even undertook to make new work in the Eastern Bloc, for instance in Bulgaria, where the unconventional woman, as an 80-year-old, went as hitch-hiker. It is only with these late works that Charlotte Pauly was able to establish herself as a heavyweight in the East German art scene. She was not adequately studied by art historians until the first decade of the 21st century, a good 20 years after her death in 1981. As early as 1990, however, her artist friend Dieter Goltzsche said: "Charlotte E. Pauly’s brittle and powerful work must be seen; no description of her life, no matter how vivid, could ever capture or explain its allure."[2]

text: Sylvie Kürsten, translation: Darrell Wilkins

[1] Dieter Goltzsche in Gallen, Sieghard: Kunst in der DDR, 1990, p. 152.

[2] op. cit.

Works by Charlotte Elfriede Pauly

Travelling exhibition

Publik machen: 40 Künstler:innen aus dem Bestand des Zentrums für Kunstausstellungen der DDR

Popular keywords

Many more works are hidden behind these terms