More Information

Read more about the exhibition

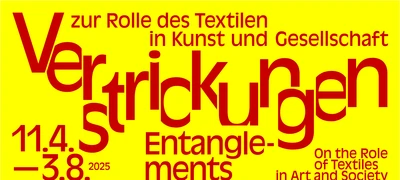

The great hall of the train station Flöha serves as site for the exhibition “Entanglements: On the Role of Textiles in Art and Society”, in which the ifa (Institut für Auslandbeziehungen) shows artists from its collection in dialogue with the local history.

Flöha, Germany

Kunstbahnhof Flöha

11.04.–03.08.

Concept

At the invitation of Purple Path curator Alexander Ochs, the ifa exhibition is presenting art works that relate to the history of textiles and explore their economic and societal entanglements. In fabric, not only do we encounter a give-and-take between tradition and innovation, we gain insight into various aspects of production, work and raw materials, of patterns and readings, which shape the world in which we live.

Textile traditions and modes of production are woven like a red thread into the fabric of the region surrounding Chemnitz: the city of Flöha, too, was an important production site for textiles from the period of the region’s industrialization through the beginning of the 1990s. Napoleon’s “Continental blockade” of 1806 and the import duties it entailed compelled weavers in the Chemnitz region to wean themselves of dependence on imported British yarn. The rivers Flöha and Zschopau in the Erzgebirge provided an ideal site for the planned weaving mills, which required significant hydropower. The first cotton-spinning mill was built in 1809. Through 1904, the complex continued to develop at a rapid pace, becoming one of the largest cotton mills in Saxony. During the GDR period, over one thousand workers passed through the Flöha train station every day on their way to the surrounding factories. The state-owned company “United Cotton Spinning and Doubling Mills” was the city’s largest employer. A few years after German Reunification, in 1994, the cotton mill closed its doors. Despite its transformation into a stock corporation in 1991, it was unable to adapt to the new conditions of the market economy. Today, the grounds of the “Old Cotton Mill” are protected as a heritage site and are developing into a new city centre.

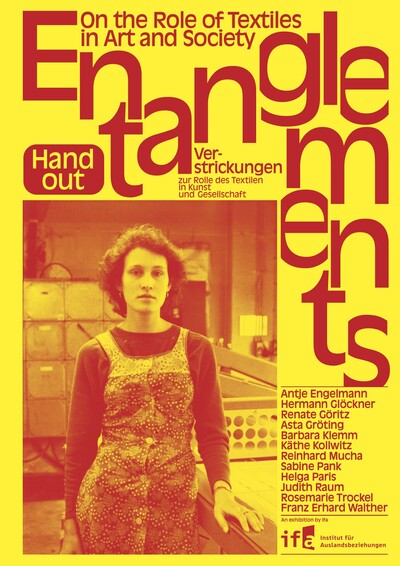

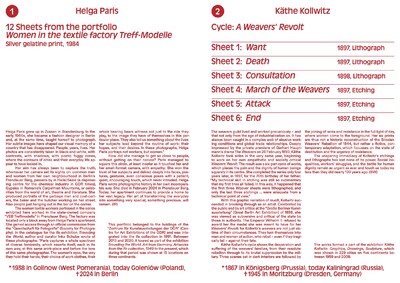

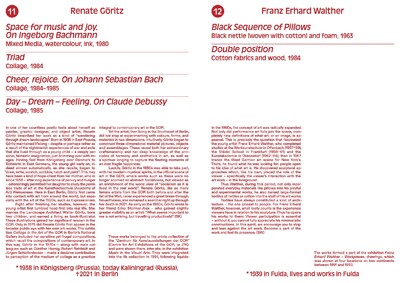

The Exhibition will bring together art works from the unique collection of the ifa, which travels all over the world. As its historic starting point, the Exhibition takes the six-part series “A Weavers’ Revolt” by Käthe Kollwitz (*1867–†1945). Kollwitz is counted among the most important protagonists of Critical Realism, and her cycle documents the precarious working conditions, the penury, and the resistance of the weavers’ guild like no other work of art. Hermann Glöckner (*1889–†1987) found his way into the art world through an apprenticeship as pattern-maker in Dresden in the early 20th century. During the GDR period, he became one the most prominent representatives of concrete art, regularly commuting between East and West. The artist Renate Göritz (*1938–†2021) counted as one of the GDR’s most prominent artists working in the medium of collage. Like Helga Paris (*1938–†2024), she lived in East Berlin and with her work helped shape the art scene there. Her large-format assemblages and collages, which, again like the photographs of Paris, come from the inventory of the Zentrum für Kunstausstellungen der DDR (GDR Centre for Art Exhibitions, or ZfK), are to be shown here for the first time since the ZfK was dissolved at the end of the year 1990. Helga Paris, after studying to be a fashion designer, taught herself to photograph in the workers’ and artists’ milieu of Prenzlauer Berg. Her portraits of female textile workers in the state-owned company “VEB Treffmodelle” go far beyond the simple representation of the twelve women who were her subjects. Rather, her images reflect that which characterizes a life: experiences, longings, and hopes. A little less than ten years later, in 1994, the West German photograph Barbara Klemm (*1939) visited the very same place in Prenzlauer Berg. Klemm, as photo journalist, has become a chronicler of societal upheavals. Besides popular demonstrations and official political meetings, she documented the last day of work at the “VEB Treffmodelle.” Her two photographs powerfully evoke emptiness and despair, but also pride and community.

In the midst of the conceptual trends of the 1960s, Franz Erhard Walther (*1939) expanded the notion of art into the performative, using textile spaces and procedural instructions. The audience enter into a relationship with his fabric sculptures and thus become sculpture themselves. Before Reinhard Mucha (*1950) studied art, he worked in a railroad supply company. This gave rise, among other things, to his great affinity for train stations with six-letter names, like Aachen or Weimar. His found mattress “Biblis” evokes associations with the city that made a name for itself through a series of accidents in the operation of its nuclear facility. Together, these two elements become a storage medium for history, a reference to something that once occurred. The artist Rosemarie Trockel (*1952) gained fame in the “wild years” of the 1980s with her conceptual panel pictures of knitted fabric. Her over-sized plaid handkerchief stands in Flöha for the notions of arrival and departure, but it also draws into question traditional conceptions of who performs what trade, and how art is produced. The sculptor Asta Gröting (*1961) uses what appear to be everyday objects and transforms them into images subject to ambiguous interpretation. Her “Affentanz” (Monkey Dance) picks up on the paradoxes of the fashion industry, by tracking the transport of leather from Turkey as a by-product of the meat industry; but her leather-jacket sculpture also stands for an image of “behaving,” which knows no beginning and no end.

The artist Judith Raum (*1977), in two video works, addresses the hierarchies present at the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau. She focusses on the development of commercial fabrics in the textile workshop of the Bauhaus: the collective work of the (female) artists on the loom is seen, by the outside world, as anonymous authorship. Judith Raum’s artistic research traces the biographies and oeuvres of designers Otti Berger and Gunta Stölzl and also narrates a story informed by the grave political caesuras caused by the National Socialists in the period of the Weimar Republic. The autobiographical investigation of Antje Engelmann (*1980) likewise sheds light on the ramifications of these crises. In her film “Eine Anleitung, um die Vergangenheit zu ändern” (Instructions for altering the past), the artist holds the magnifying glass to her own family history. Migration and tradition are in the DNA of the Danube Swabians. Traditional dress, a link between generations, was like a second skin to her great-grandmother Hermine. At the end of her film, the artist herself slips into the dress, in order to question the cycle of passing it on.

Likewise included in the Exhibition is the four-part textile collage “Landschaft, Schlichten, Zwirnen, Endprodukt” (Landscape, Dressing, Doubling, End Product), which Sabine Pank created in 1983-1984 for the Boardroom in the executive administration building of the cotton spinning mill in Flöha. Pank articulates artistically the path of cotton as it is transformed into yarn, using silk collages. Upon liquidation of the Sächsische Baumwollspinnereien und Zwirnereien AG (Saxonian Cotton Spinning and Doubling Mills Ltd) by the Treuhandanstalt in 1991, the cycle was moved to the Administrative Headquarters of the Spinning Mill Venusberg. The convoluted history of the textile industry in this region also forms the subject of the wall journal in the passageway to the train station’s tunnel. This work was conceptualized by Mike Huth and designed by Jakob Kirch. At the end of the year, the Old Cotton Mill will open a permanent exhibition on the history of the textile industry in Flöha.

Ed.: Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen e. V. (ifa)

2025

german/english

14 pages

29,5 x 21 cm

Texts: Susan Börner, Sylvie Kürsten, Judith Raum, Tobias Rosen, Ingeborg Ruthe, Susanne Weiß

Proofreading: Susan Börner, Susanne Weiß

Translation ger/en: Darrell Wilkins

Exhibition views Kunstbahnhof Flöha