Michael Morgner

- * 1942

Life dates

- Artist

Category

Erect Striding Proteus on the Southern Edge of the Zone

The graphic artist, painter, sculptor, and action artist Michael Morgner, born 1942 in Chemnitz (then Karl-Marx-Stadt), is among the last protagonists of a fast-disappearing generation of artists from East Germany: an acknowledged icon of non-conformity both before and after the fall of the Wall, but never one of those stars that the art industry really needs and courts.

Soon after completing his art degree at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst in Leipzig (1961– 66), Morgner returned to the model socialist industrial city of Karl-Marx-Stadt and founded, together with other resident artists, the Galerie Oben, which was for a period one of the most important non-state art spaces in the GDR. As member of the cooperative gallery’s artistic advisory board, Morgner shaped its program and exhibited his work there on numerous occasions. His work, despite the variety of media employed – from ink drawings and graphic print series to latex painting and his own leaching technique of lavage – revolves around a clear, motif-based thematic core: Ever since his treatment of Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a portfolio of graphic works from 1972, Morgner devoted himself to styling a universal principle of transformation, to which all life is subject. Whether he was sketching archaic-abstract constellations of signs or human figures, which are reduced to linear structures of sinews and bones and thus become emblems of psychic states – Morgner’s art, with the incantation of a prayer mill, recounts narratives of departures, absence, homecomings, and death. In spite of these deeply existentialist, often religiously (passion-) inspired themes, Michael Morgner is known for his intractable-humorous spirit of resistance to any form of instrumentalization and to the pseudo-intellectualizing of art.

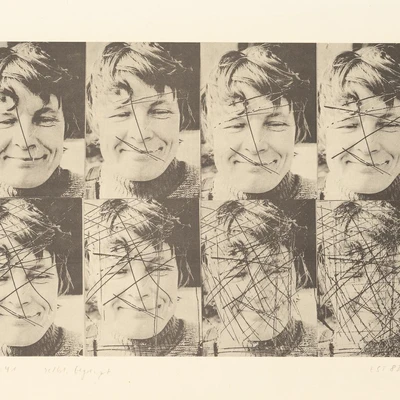

Instead of pious-credulously gawking, he wants to laugh the country awake with art – thus does Morgner himself describe his mission. This humor was evident not only in his dealings with the as many as 140 Stasi informants who targeted in particular the avant-garde artist group and producer gallery Clara Mosch, which he co-founded in 1977, and which sought, from its locus on the fringes of Karl-Marx-Stadt, to push the boundaries of what could be said and shown art-wise in the GDR. It appears more than anywhere else in the collective action-art events held in the boondocks of Socialist Germany, which used playful-performative tactics to address taboo subjects such as destruction of the environment. Again and again, Morgner took advantage of these events to launch spectacular one-man shows: Along with the action-art performance Kreuz legen (Laying the cross – laying the trap) on the island of Rügen, the acme of Morgner’s career as action-artist was his Seeüberschreitung bei Gallentin (Walking on water at Gallentin). This photo- and video-performance, which Morgner later re-worked in paintings, and which modulates between abstraction and figurative art, between high culture and pop culture, made him into an icon of multi-media art in the GDR.

Morgner also skilfully danced back and forth between the official and non-official art scenes. He received public commissions, such as that for the outdoor mural Gießprozeß – der arbeitende Mensch in unserer Gesellschaft (The casting process – man at work in our society) or the sculptural environment Die Nacht (Night) for the Staatstheater Dresden. A father of four children, Morgner was permitted to travel from the GDR to both socialist and western foreign countries and to exhibit there.

In spite of these advantages, Morgner was a strident opponent of the socialist-realism doctrine of art. In 1984, he resigned from the board of directors of the regional Verband Bildender Künstler and in 1988 refused to participate in the 10th Art Exhibition of the GDR. Even during and after the dissolution of the GDR, Morgner continued to work with his symbolic figurative aesthetic, although he began to create large-format mixed-media collages and triptychs or panels. After the citizen rights association Neues Forum declined to accept his Striding Man as a signet, he had the work cast larger than life in steel and therewith became a sculptor, too.

Despite that Michael Morgner’s work has been displayed since 1989 in numerous solo and group exhibitions, that he was awarded the Bundesverdienstkreuz (German Federal Cross of Merit) in 2023, and that he belongs without a doubt to the most important artistic protagonists of his generation, Michael Morgner still feels he has been neglected. In his view, a genuine reunification among the artists of Germany – especially those of his generation – never really took place.

text: Sylvie Kürsten, translation: Darrell Wilkins

Works by Michael Morgner

Travelling exhibition

Publik machen: 40 Künstler:innen aus dem Bestand des Zentrums für Kunstausstellungen der DDR

Popular keywords

Many more works are hidden behind these terms