Dieter Tucholke

- * 1934

- † 2001

Life dates

- Artist

Category

Man and History

How can we use images to adequately relate what has occurred and counteract the will to let history slip quietly into oblivion? This is the question, and the challenge, that artist Dieter Tucholke posed himself throughout his entire oeuvre. In one of his first material prints from 1965, we already see Tucholke searching for new technical possibilities, with which by way of memorialization he can ban to the two-dimensional image a man-made terror which must never be repeated in life.

Dieter Tucholke, born 1934 in Berlin and deceased there in 2001, studied the graphic arts from 1952 to 1957 with Werner Klemke and Arno Mohr at the Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weissensee. In his artist colleagues Ingo Kirchner, Robert Rehfeldt and Hanfried Schulz, he found kindred spirits who would accompany him in his search for new, experimental forms of expression. With an evident joy in experimentation, he produced, starting ca. 1967, material pictures, collages, assemblages, and later objects and paintings that reveal an affiliation with Dada and Constructivism. In its subject matter, his art consistently addresses the societal conflicts and dangers posed in the past, present, and future.

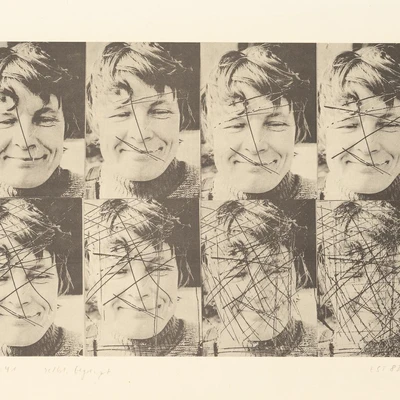

Tucholke did not just employ the various printing techniques with masterly precision, he also combined them so as to render the complex web of relationships in his subject matter visible. In his engraving Henker (Hangman, from 1967) or his series of Köpfe (Heads), he sought, by overlaying various levels of image, print, and color, to achieve a dramatic narrative form, which conveyed itself to the viewer. The individual physiognomy of the Hangman is obliterated by the picture’s symbolism of the most inhuman ideology. Owing to the bursting of their structures, his Heads are recognizable only as outlines, as spirits, on the paper. Through the “collage-like pilings of virtues and vices” (Dieter Tucholke), the artist questions the causes of hostility, suffering, and passion. In formal and conceptual overlays, he bores into the heart of petty-bourgeois modes of conduct.

What follows forms a part of his critical analysis of German history, one of the central motifs of his artistic output. Especially in the comprehensive series of offset lithographs entitled Negativbilder –Preussische Geschichte (PrintNegatives – Prussian History, 1979–1981), Tucholke draws a complex psychological portrait of a morbid form of rulership, which continues to exert a malignant influence on society even today, and which culminated in an even more awful expression – one that Tucholke addresses in the graphic portfolio Die Nacht hat 12 Stunden – ein Totentanz (1933–1945) (The Night lasts 12 Hours – a Dance of the Dead (1933-45) ). Comprising 20 works that combine the media of color silkscreens with etchings and writings, this portfolio attempts to convey in graphic form, and uncompromisingly, the twelve darkest years in German history.

Politically engaged and yet perceived as a disturbing presence in the context of the GDR cultural landscape, Dieter Tucholke appropriated the Avant-Garde movements of the 20th century and carried them forward, from his specific perspective and with his multifarious artistic means of expression, into his own day and into the future. Taking the graphic medium as his starting point, he constantly expanded his repertoire: Besides objects and painting (from 1983 on), he also integrated photography, projections and sound into his works. The result was a many-layered oeuvre, populated by images that incisively comment on history and mirror and critique the present day.

text: Anke Paula Böttcher, translation: Darrell Wilkens

Works by Dieter Tucholke

Travelling exhibition

Publik machen: 40 Künstler:innen aus dem Bestand des Zentrums für Kunstausstellungen der DDR

Popular keywords

Many more works are hidden behind these terms