Carlfriedrich Claus

- * 1930

- † 1998

Life dates

- Artist

Category

The Draughtsman Philosopher from the Erzgebirge

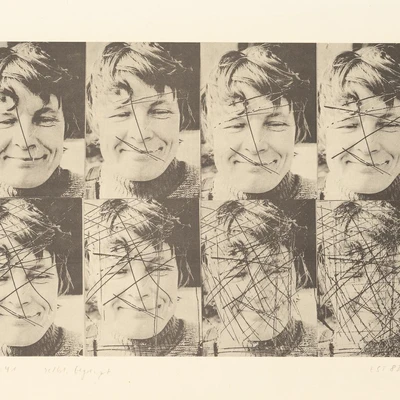

Carlfriedrich Claus was born 1930 in Annaberg-Buchholz, in the region of the western Erzgebirge. An autodidact, he developed there his avant-garde, utopic artistic cosmos. In the Mauerland, he became known as an internationally networked co-founder of visual poetry. He stood quietly and carried on a correspondence with artists and thinkers all over Europe, in particular with Ernst Bloch, whose Prinzip Hoffnung (The Principle of Hope) gave Claus a decisive impulse in the creation of his ambitious series of drawings Das geschichtsphilosophische Kombinat (The History and Philosophy Combine). He created delicate works on transparent paper, which he covered densely on both sides with drawings and writings, so that the lines create webs and layerings, and intimations of figures or landscapes appear. Many of Claus’s contemporaries, especially those with little affinity for art, considered him eccentric. He himself viewed his own Sprachblätter (language graphics) – which he created as a marginal zone of literature with his thinking hand and his writing hand, as he put it – as unreadable in the usual sense of the word. Within the rigidly defined limitations of Socialist art, in any event, there was no place for this highly complex oeuvre. Thus there was little public resonance for Claus’s work within the GDR. He was a member of the subversive artist group Clara Mosch, which flourished in Karl-Marx-Stadt (later Chemnitz).

The artist-philosopher Claus died young in 1998. In the period immediately after the fall of the Wall, however, he won prizes and found collectors; he was made a member of the Akademie der Künste, he was awarded the Bundesverdienstkreuz (German Federal Cross of Merit). This universalist speech artist and draughtsman left behind a Gesamtkunstwerk composed of sound formations, phonetic processes, and poetry as experimental as it is sensual. He also passionately investigated underlying affinities at the crossroads of ethics and aesthetics. His work contains many a complex excursus negotiating between Marxism and humanism, among Paracelsus, Goethe, Eluard and Bloch, among Christianity, the Kabbala, Zen-Buddhism and cybernetics. For Claus, who bequeathed his life work inter vivos to the city art collections of Chemnitz under the rubric of the “Claus-Archive,” art served an “utopic function.” His vision of the equality and rights and happiness of all human beings quaffed, in his view, from an infinite, unfathomable “thinking space,” and expressed itself in an almost religious appeal for “the naturalization of man and the humanization of nature.”

text: Ingeborg Ruthe, translation: Darrell Wilkins

Works by Carlfriedrich Claus

Travelling exhibition

Publik machen: 40 Künstler:innen aus dem Bestand des Zentrums für Kunstausstellungen der DDR

Popular keywords

Many more works are hidden behind these terms